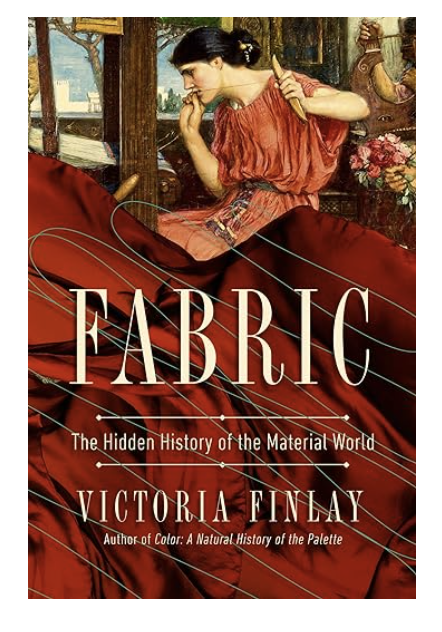

Victoria Finlay’s Fabric: The Hidden History of the Material World is itself a beautiful tapestry of a work, woven together to unfold a hidden but powerful history of fabrics. Yet the book is more than a history of fabrics—it draws out the human spirit and culture deeply embedded in fabric making, from simple sewing to more technological production. Finlay gives the right amount of context for every part of the narrative, including key major historical moments that have shaped fabric production and development. The book includes tidbits on mythology, spirituality and theology, which adds further dimension and enrichment. To top off the pattern, the author shares her own vulnerability as she undergoes a journey of healing from the recent loss of her parents.

In her work, Finlay gives us a generous portion of fabric sampling such as, but not limited to: Barkcloth, which “emerges fully formed from the tree; the design of it emerges fully formed from its maker’s mind” (56); “Cotton has this lightness, this quality of being drawn into fine threads, that is like its magic” (74); Pashmina: “pure pashm is only from the belly” (203); Silk: “Other natural fabrics—linen, jute, hemp, cotton, barkcloth, horsehair, wool—come from a crop, a growth event, a haircut. But silk? Silk is a miracle” (377); Sackcloth: Besides its practicality in containing things “sackcloth has a secondary reputation. It’s the fabric of penitence” (245); Linen “in a way is the purest fabric…it was also the fabric that priests wore” (298). These fabrics have undoubtedly held powerful clout in the history of humanity.

Fabrics have proven to be a major powerhouse, enabling great feats and helping to overcome financial difficulties. Multiple inventors, entrepreneurs and visionaries have been involved with fabrics, and worked to develop and tweak machinery to further expedite fabric production. Some of these individuals stood in the background but nevertheless planted the seed while others built on it. Furthermore, fabrics allowed for countries to move forward. For example, while other countries were experiencing issues with their silk supplies, “it was raw silk that helped Japan control its runaway inflation…[and] build up a trade surplus…silk kept delivering” (373). In addition, fabrics have served to push forward the economy in many different ways; for instance, by enforcing that certain clothing be worn for different purposes, the need for fabrics increased.

Just like fabrics have been interwoven in human lives since the beginning of time,Finlay also infuses her fabric journey with her personal healing journey, her humanity being the stitch that holds both parts together. She carries the memories of her parents near and dear. Her mother especially, though deceased, becomes very present in her journey: “the scene…fell away as if it was itself a dream, and to my surprise I found myself talking to my mother” (65). The book journeys through various parts of the world, even stopping at past points in time. She is not only an observer but a willing participant, which is human experience at its core. She is not afraid to try, even if she fails: “ ‘Mould it between your fingers,’ she says, sighing at my ineptitude…And she shows me again. And again. And again…I still can’t spin. But I have learned something about connecting” (73). Finlay lets us sit with her, walk with her, observe with her and learn with her. We overhear conversations that she has with various people, which proves to be fundamental to her journey of learning and discovery.

The theme that permeates the book is how things are connected, bringing different elements—culture, etymology, fabric making, storytelling—together. For instance, “in India, many sacred words are also textile words. Tantra, or sacred text…suggests patterns that are woven. Sutra, or sacred saying…[is] an allusion to connecting ideas. Grantha, meaning script or holy book, is from a word for knotted thread” (81). Throughout her journey, Finlay discovers the intimate connection and spirituality embedded in the fabrics themselves used to make clothing. She writes, “clothing was not just about fashion or display or prestige or practicality or even rank. It was, sometimes, about achieving an actual connection, through material, to a world beyond the material” (352). Besides the spiritual beyond the material, the one cannot separate fabrics from the people and the culture. In fact, the origination and development of clothes has been in direct conjunction with people and culture. Thus, nothing exists in complete isolation; one idea, event in time or person/persons affects another and the cycle continues.

While the book presents a lightness to the world of fabric, it does not obscure the dark side of the industry. Various practices in fabric production have been unjust; poor working conditions, issues of slavery and child labor are all costs that are too high. Furthermore, technological advances have been a blessing and a curse. Much like today, technology may automate certain processes but also leaves people without jobs. Another relevant issue to be noted is the harmful effect that certain materials have on the environment. In the same vein, Finlay discusses how fabrics may be repurposed or upcycled. Lastly, though many women have faced hardship in working with fabrics, fabric has also given women a voice and the ability to rise above their circumstances.

Although a hefty book, Finlay engages the reader through personal trajectories, keen observations, interesting historical narratives and illustrative examples. Reading this book was like being on an adventurous trek with the author—I was there as she picked up various tools to work with materials, explore the lands, talk with various people, and was simply present in every moment. This book turned out to be an enjoyable read and a deep learning experience. It enriched my understanding of the unraveling of fabrics and even for history itself. It opened my eyes to the hidden history of the materials by which we come to clothe ourselves and gave me a deeper appreciation for the intricate ways that fabric exists in our lives.

Original review: https://englewoodreview.org/victoria-finlay-fabric-review/